A reparative transfer is a wealth transfer given directly to Black Descendants of Enslaved Americans from the Reparation Generation. This wealth transfer is not a donation or gift. While we understand the importance of philanthropy in advancing valuable programs and causes, making a Reparative Transfer is a conscious and intentional acknowledgement and way to reconcile the ways you, and perhaps your family, have benefited historically from slavery and ongoing structural racism.

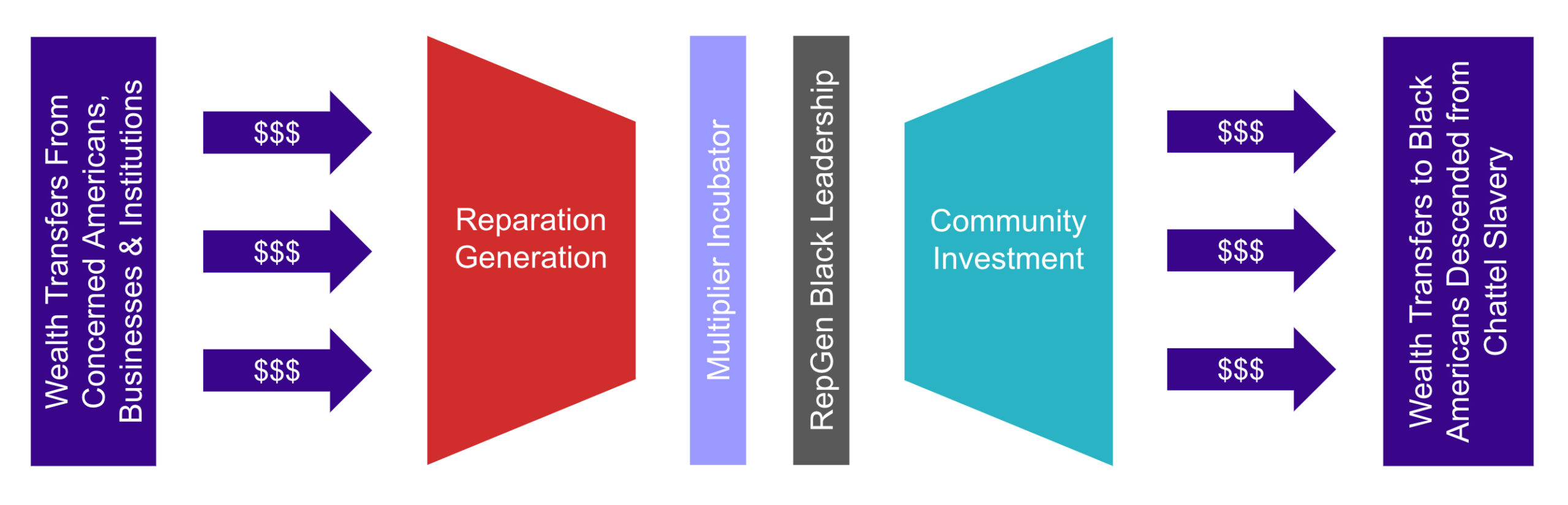

Anyone can financially support Reparation Generation. We raise funds from individuals, corporations and foundations for our initiatives to fund reparative transfers to Black Americans for wealth-building pursuits.

Yes, Reparation Generation is a project of Multiplier, a tax-exempt nonprofit 501(c)(3) umbrella organization (tax ID 91-2166435).

No. We appreciate contributions of any amount.

You can expect the following once you’ve financially contributed:

Reparation Generation has relied upon Birth Records, Death Records, Personal Family Trees, DNA testing, as well as other attestations of family history. Any Black person who can trace their heritage to people enslaved in the 48 contiguous United States is eligible for our reparative transfers program.

Homeownership comprises the largest portion of Americans’ wealth, yet has been consistently less accessible to Black citizens. Reparation Generation (RepGen) believes that the American Dream of homeownership is a pathway to generational wealth that will address America’s racial wealth gap as well as generate a sense of stability, place and belonging. While our ultimate goal continues to be a Federal Reparations Act, we aren’t waiting for our government to act. RepGen’s founders set out to demonstrate reparative models that cultivate intergenerational wealth for Black people who descend from enslaved Americans. One model we are demonstrating and evaluating focuses on direct Reparative Wealth Transfers to Black Americans for Homeownership. Learn more about RepGen’s Homeownership Reparative Transfer (HORT) Program

Detroit’s complicated racial history illustrates the array of issues underlying racial injustice and disparity in America. As a city that saw a large number Black migrants during the great migration, Detroit is the home to direct descendants of enslaved Americans and those targeted by Jim Crow laws in the South. Structurally racist policies and practices in Detroit, like redlining and race-based housing covenants, served to segregate and economically oppress Black residents. The effects persist today: Detroit’s population, job, and housing markets mirror those in other industrial Great Migration cities like Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Baltimore, making it a good location to demonstrate the impact and scalability of Reparation Generation’s initiatives.

A significant example of government-sanctioned racism in Detroit is the demolition of the Paradise Valley district and Black Bottom neighborhood. From the 1920s to the 1950s, Black Bottom—an area already home to diverse immigrant populations—was one of the few Detroit neighborhoods where housing covenants permitted Black residents to reside. The Great Migration brought thousands of Black migrants fleeing the Jim Crow South in search of jobs in the automotive industry. Paradise Valley was known for its thriving Black music scene and a number of Black-owned businesses, including several restaurants, grocers, medical providers, churches, and nightclubs.

In the late 1940s, Detroit leaders began planning “urban renewal” projects in the area, using National Housing Act funds to demolish older buildings; in the mid-1950s, the National Highway Act provided funds for the construction of freeways through the area to connect Detroit’s industrial hub with the growing population of suburban, predominantly white workers. The neighborhoods’ diversity and lower tax base made them prime targets for renewal and demolition. By the early 1960s, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley had been replaced by the Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park, a middle-income residential and business district. Former residents were displaced throughout the city, often to nearby housing projects. The demolition of these neighborhoods erased significant aspects of Detroit’s Black culture, history, and wealth. Today, the city is striving to reclaim its place as a hub of Black innovation and prosperity. (Reference: information here)

Reparation Generation is just one thread in the fabric of the Reparation tapestry. We are committed to working with other Reparative Justice programs in a movement that will lead our nation to a Federal Reparations Act. However, right now, individuals, corporations, and foundations that are ready to reconcile history and to atone for slavery and its legacy can immediately impact the racial wealth gap by making reparative transfers through Reparation Generation. The Reparative Wealth Transfers will go initially to homeownership, but we will also expand into addressing education and business ownership barriers. This process will allow for healing of our nation and provide real evidence of the demand for and the power of reparations.

Black descendants of enslaved Americans have endured the most profound harm from slavery and its enduring legacy. While other groups of Black people have faced significant challenges, those with enslaved American ancestors uniquely carry the generational trauma of having sacrificed the most to build America, yet having benefited the least. Our focus honors the pioneers who initiated the movement for Black reparations and their descendants, who continue to seek justice and repair for these historical wrongs.

We have an ethical responsibility to ensure that those who have suffered the most from the legacy of slavery are the ones guiding and controlling reparative efforts.

By being a Black-led organization, we ensure that the voices, experiences, and perspectives of those directly impacted by slavery and its ongoing consequences are at the forefront of our work. This leadership is not just symbolic; it is crucial for driving authentic, effective, and meaningful change that truly addresses the historical and systemic injustices faced by Black descendants of enslaved Americans.